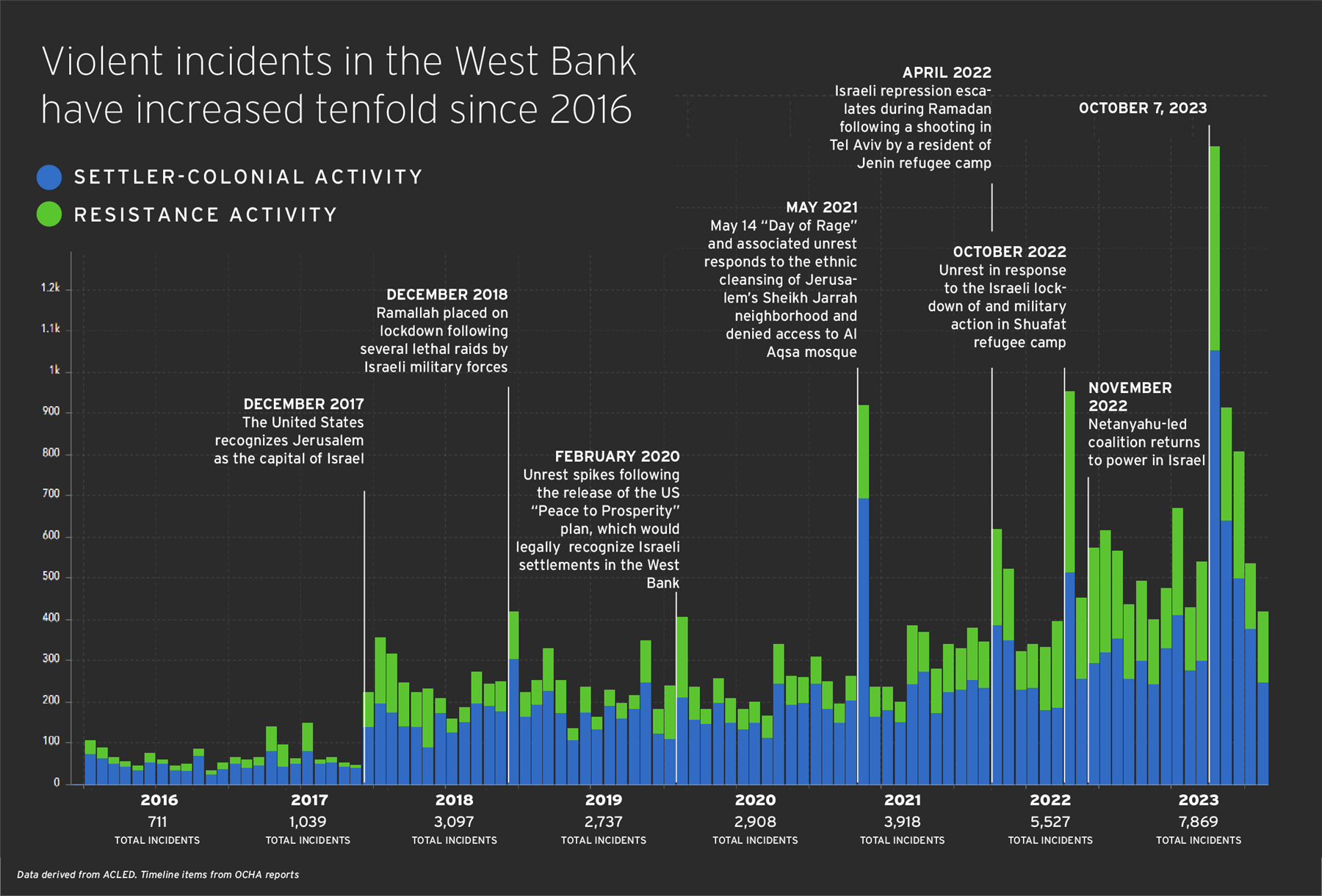

Violence against Palestinians in the West Bank has increased tenfold since 2016, yet the day-to-day oppressive enactments of Israel’s unlawful occupation generally get little media attention— a problem exacerbated by Israel’s current genocidal campaign on the Gaza Strip. This violence, however, is highly consequential in how it reshapes the remaining swathes of Palestine and constrains its inhabitance for Palestinian communities.

This analysis, and the monitor it is based on, confronts the claim that this conflict is a “cycle of violence”, tribal in nature, occurring between equal parties, and essentially endemic to the region. Rather, this research galvanizes the urgent need for greater scrutiny of Israeli actions across all of Palestine.

The monitor may be found at bit.ly/westbankviolence.

Context

Before delving into the project proper, it is important to understand the history and nature of the terrain in which it unfolds. The West Bank of the Jordan River is home to some three million Palestinians, a population whose settlement hails back to the 15th century B.C.[2] Interspersed among the rolling hills, fields, and ancient cities like Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Nablus are 19 refugee camps, inhabited by families and descendants of those who were forced to flee their ancestral homes and villages during the wave of ethnic cleansing concomitant with the founding of the state of Israel in 1948.[3] Overlapping with this historic inhabitance is the expansionist project of Zionist settler colonialism that seeks to uproot the land of its inhabitants and replace them with Jewish Israelis.[4] Since 1967, which witnessed a second exodus of Palestinians and the military occupation of the West Bank (and the Gaza Strip), the expansionist process has sought to systematically encroach over more Palestinian land, encircle its communities, separate people from agricultural fields, and strategically appropriate territories and resources while displacing long term dwellers. As settlement construction continues unabated, the occupation’s dual strategy of ethnic cleansing and apartheid[5] is enforced through a well-documented set of spatial, social, and legal structures. A 708 km separation wall cuts through the West Bank where Palestinian communities are carved with segregated streets to which they have no access; hilltop settlements dot the territory and generate control from high ground;[6] a network of Israeli checkpoints constrains the movement of Palestinians; and the risk of their arbitrary arrest constantly looms whereby a child as young as fourteen could be detained indefinitely without charge and prosecuted in Israeli military courts.[7] These forms of occupation, and the networks of militarized security that support them,[8] form the backdrop against which the violent incidents documented in this monitor need to be read.

Today, countryside, camp, and city alike are sites of new waves of this routinized violence often deemed “senseless” in the dominant narratives of western media. We argue that this violence has a logic, that this logic needs to be unraveled, and that it can only be understood against the background of a 100-year unfolding process of colonizing Palestinian land and displacing indigenous non-Jewish populations.[9] To be sure, no dataset can reflect the multiplicity of ways in which Palestinians are subjected to ethnic cleansing. Yet, by disentangling overlapping forms of violence, sequencing them, attributing them to specific actors, and locating them in time and space, this monitor offers insight into the structured and asymmetrical nature of violence in the West Bank.

Methods

The premise of this research is that the multiple forms of violence are integral to maintaining a regime of occupation. To inquire into the nature of these forms, the parties that enact them, and the political shifts they signal, the Beirut Urban Lab adapted data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). ACLED collects and regularly publishes comprehensive data on violent incidents from around the world, primarily from journalistic sources, resulting in a robust and up-to-date dataset that is ambitious in scope. Data collection in the West Bank is given additional care to address, according to ACLED, the censorship-ridden media environment of the region and what they consider to be “contrasting biases”.

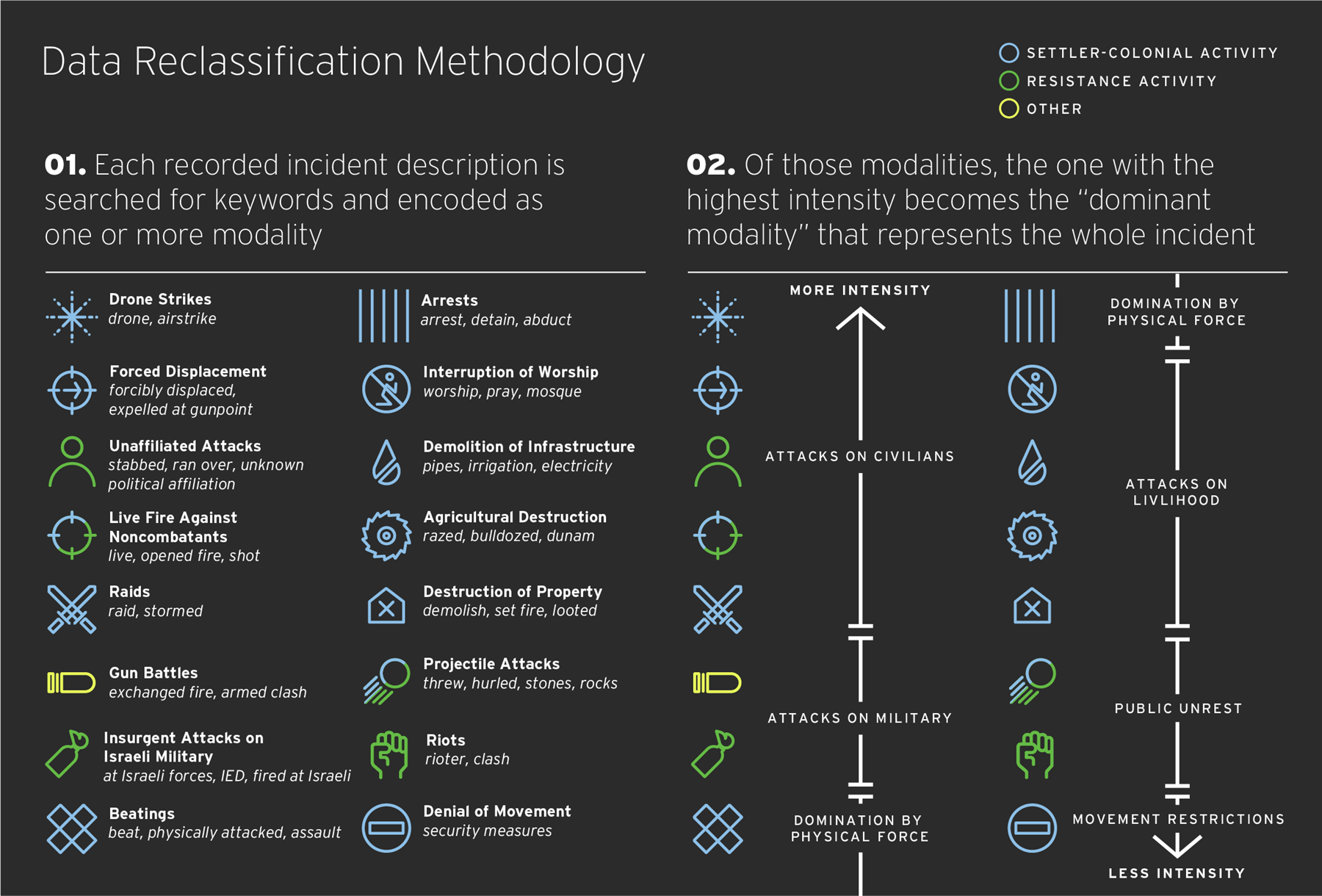

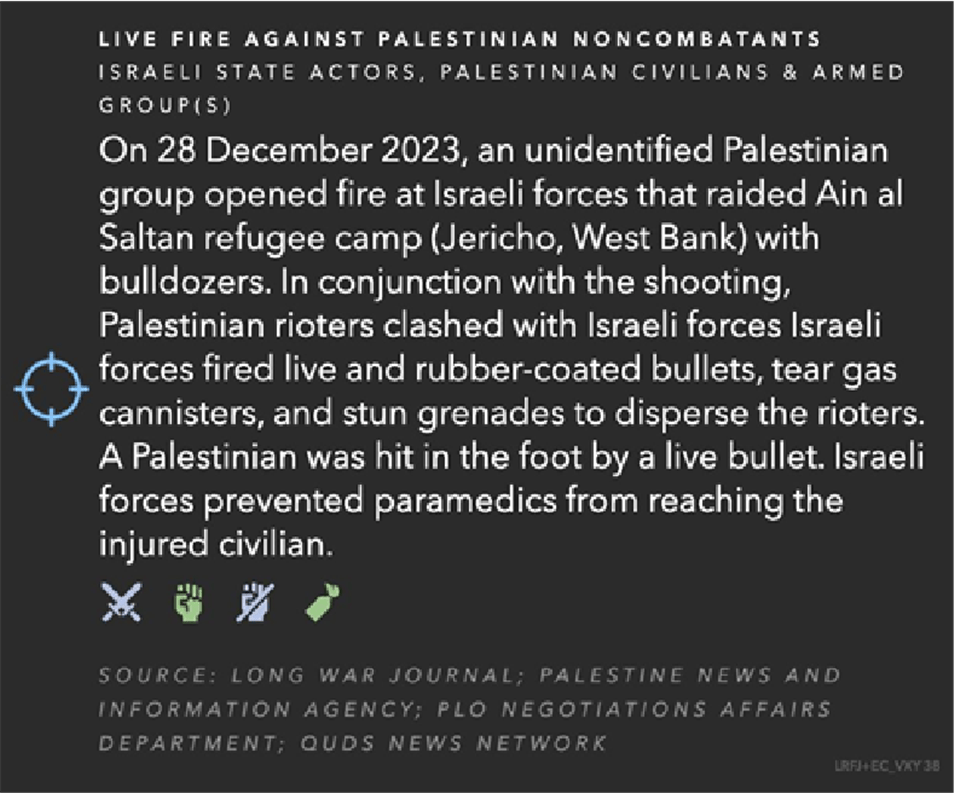

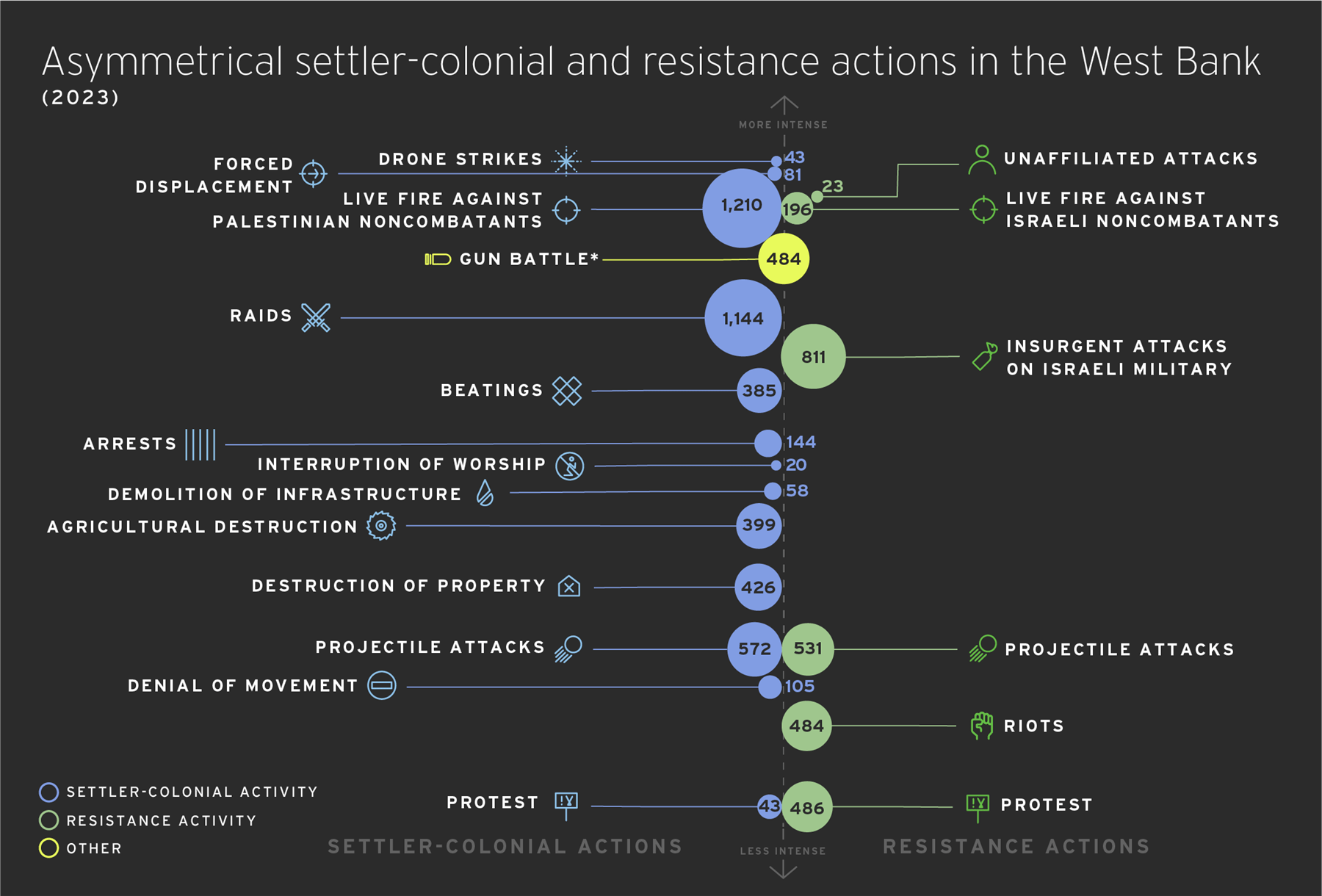

In adapting this data, the Lab’s critical mapping team operated from the principle that so-called “objective” or “impartial” modes of processing and interpreting reported actions can inappropriately homogenize incidents of violence and mislead readers.[10] Instead, the research adhered to an approach that allows the context of an ongoing, militarily enforced settlement project to illuminate the data processing and to shape its visualization. Thus, the work of spatially locating the dominant modalities of violence being enacted in the West Bank, the development of an iterative keyword recognition process to reclassify and disentangle those modalities, and the task of attributing those modalities to the agency of specific actors all proceeded from that core assumption. To give one example of how this manifests, stone-throwing cannot be interpreted the same way when practiced by Palestinians as by Israelis, when stone-throwing by Palestinians was met with tear gas and rubber bullets 72% of the time in 2023 while Israeli stone-throwers did not encounter a single instance of similar repression. Here, discriminatory enforcement renders important qualitative differences in how Israelis and Palestinians practice what is superficially the same act. An apprehension of these differences necessitated adopting settler-colonial and resistance activities as the primary classification of the data. The unique spectrum of violence arising under an occupation also dictated a novel classification of categories, or modalities of violence specific to the context of the West Bank (Fig. 1).[11]

Long Term Escalation

Locales

Asymmetry

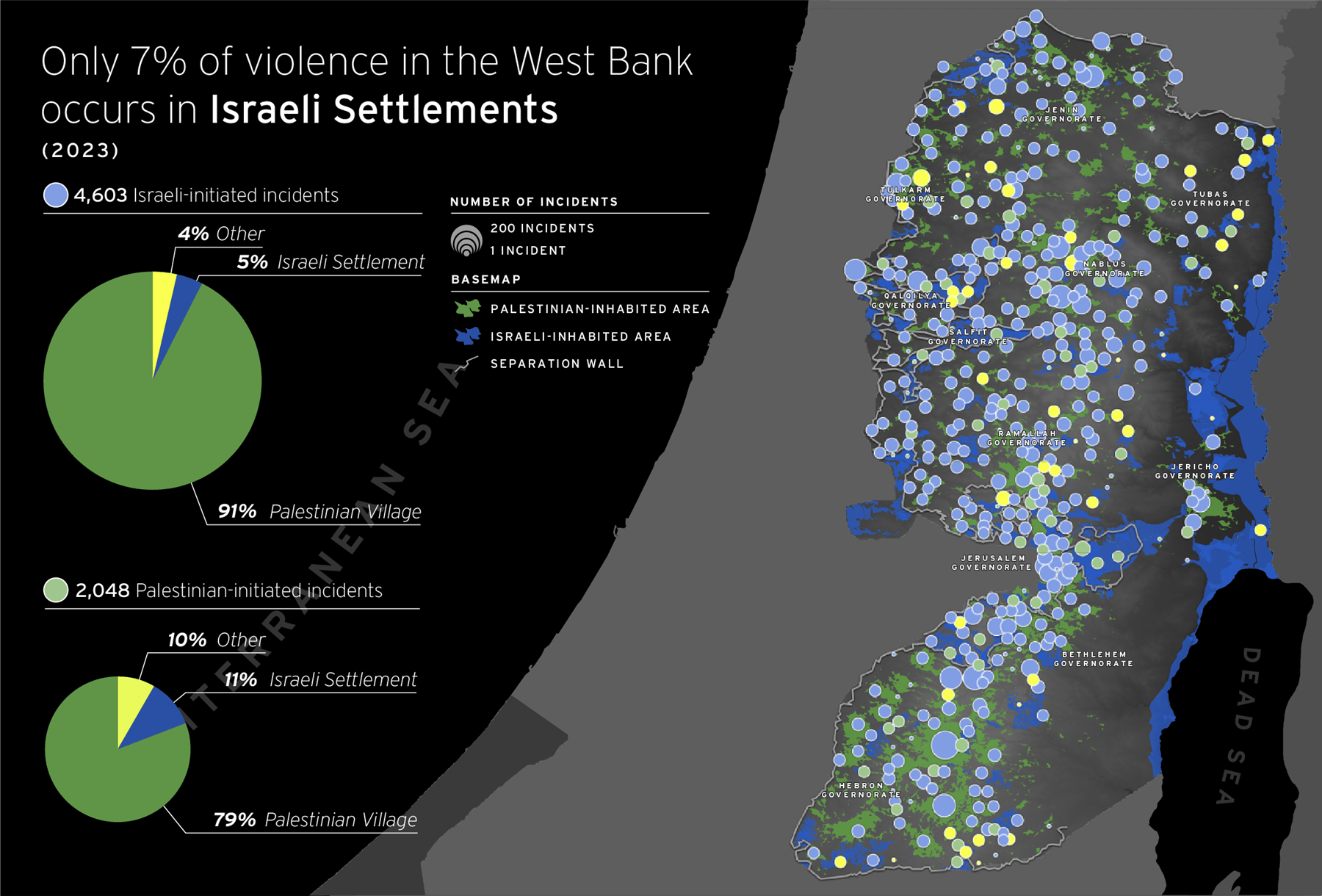

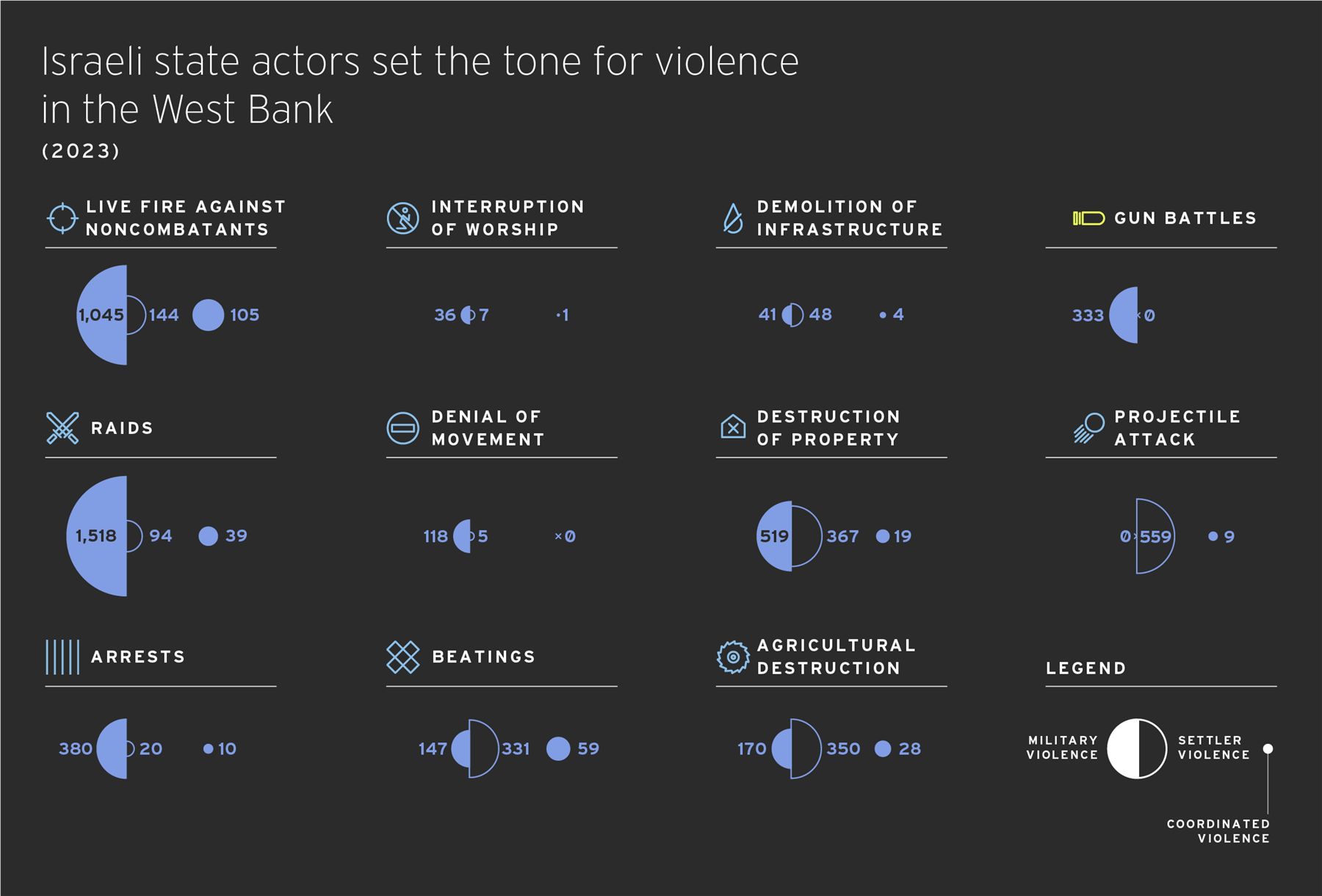

The asymmetry extends beyond localities and into the modalities of violence. Of the 17 total modalities we identified, 3 are exclusively practiced by Palestinians, 3 are practiced by both sides, and 11 are exclusively Israeli – reflecting the uneven distribution of autonomy produced by the occupation (Fig. 5). Parsing the data, one does not read about the razing of Israeli farmland to make way for a new Palestinian village, or the hospitalization of an Israeli child after he was physically beaten by Palestinian soldiers during a raid, or Palestinian civilians attacking Jewish worshippers with pepper spray at shul. Superficially, there were 5 Israeli-initiated activities for every 2 Palestinian-initiated activities in 2023. However, this comparison fails to capture the multiple differences in the ways this violence is experienced and enacted. The most common form of resistance violence, insurgent attacks, exclusively target the Israeli military, whereas the most prominent forms of settler-colonial violence, such as live fire against unarmed Palestinians and raids of Palestinian communities, have more vulnerable targets.

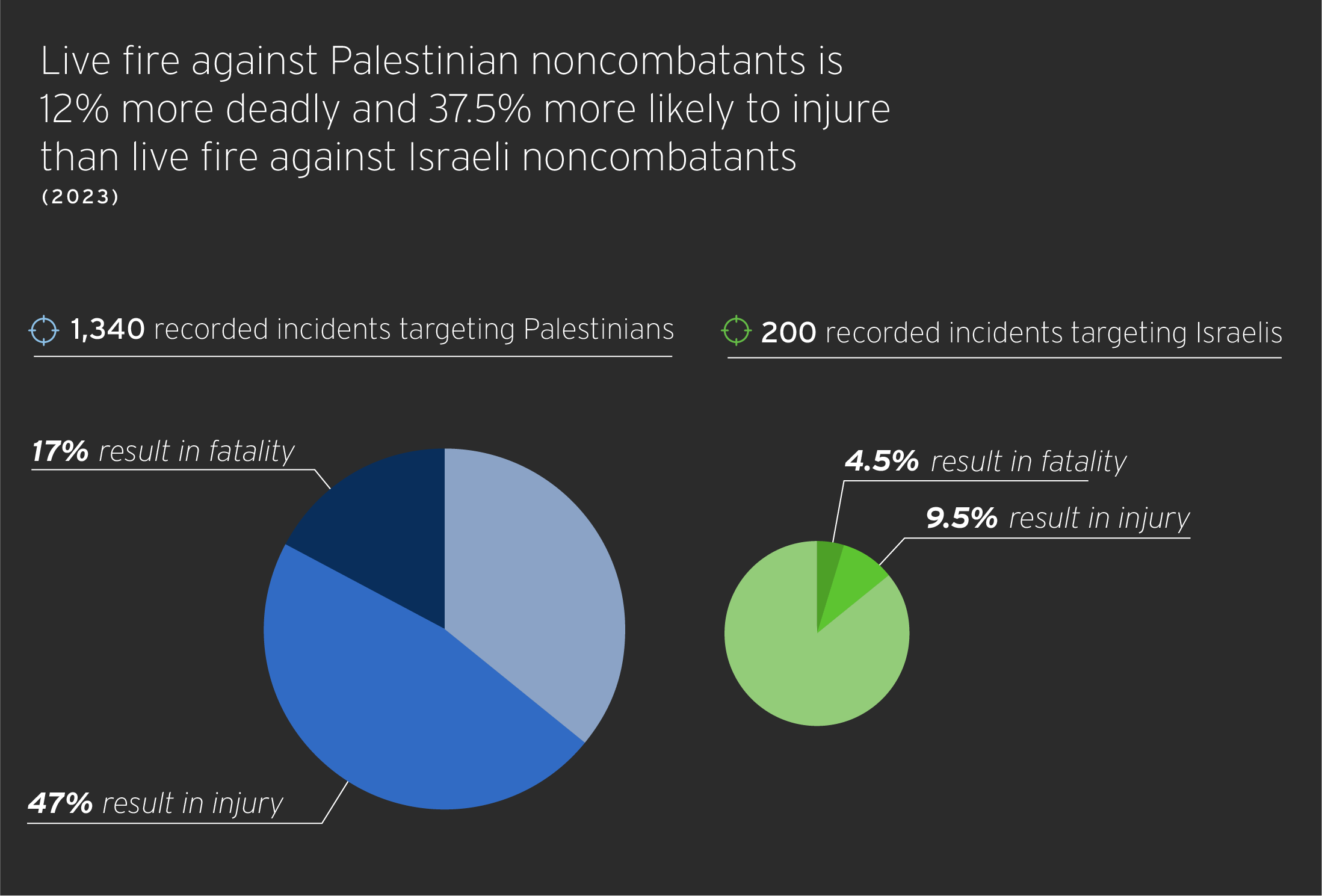

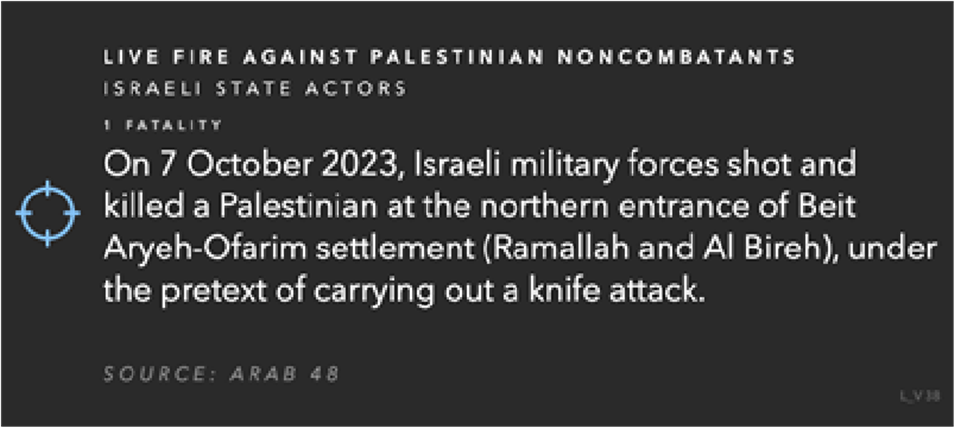

Israeli violence is qualitatively more severe in scale, context, and effect than Palestinian violence. For example, in 2023 there were 1,340 reported cases of live fire against Palestinian noncombatants, far out of scale with the 200 cases of live fire against Israeli noncombatants (Fig. 6). An examination of the contexts of these shootings further differentiates them. 71% of shootings against unarmed Palestinians occur alongside tear gas and stun grenades, and often seem to serve as crowd control during Israeli raids (Fig. 7). 28% have even more questionable justifications, such as “standing near the separating wall,” (Fig. 8) and a handful occur under the pretext of stopping violence such as alleged car rammings or stabbing attempts (Fig. 9).

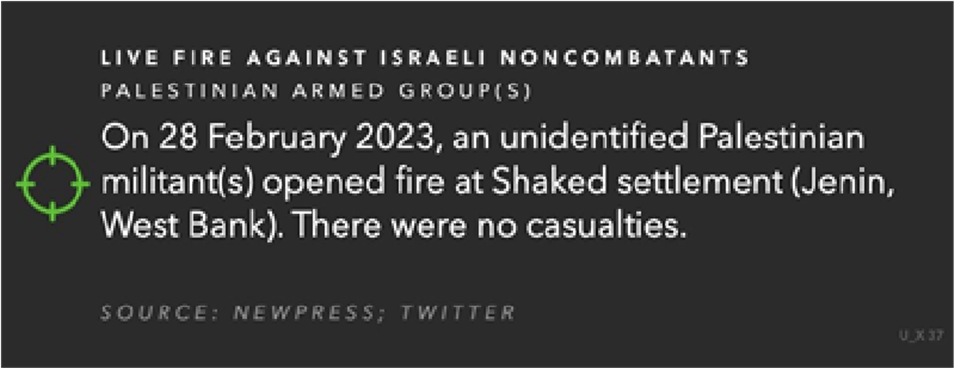

Meanwhile, 79% of cases targeting Israeli noncombatants were instances of Palestinian armed groups shooting “towards” or “near” a settlement, with no particular human target or targets mentioned (Fig. 9). The effect of this distinction between live fire from an occupying army with total superiority and live fire from “hit-and-fade” insurgent attacks is clear in the casualty rates. Live fire against noncombatants killed 9 settlers and injured 19 in 2023, while it killed at least 252 Palestinians including 19 children and injured hundreds over the same period. Compared directly, live fire against Palestinian noncombatants is 12.5% more deadly and 37.5% more likely to injure than the inverse. Such shocking numbers are unthinkable in similar contexts, such as that of a police force against a citizenry. Yet these are not domestic incidents, but rather the actions of a foreign army against civilians under occupation.

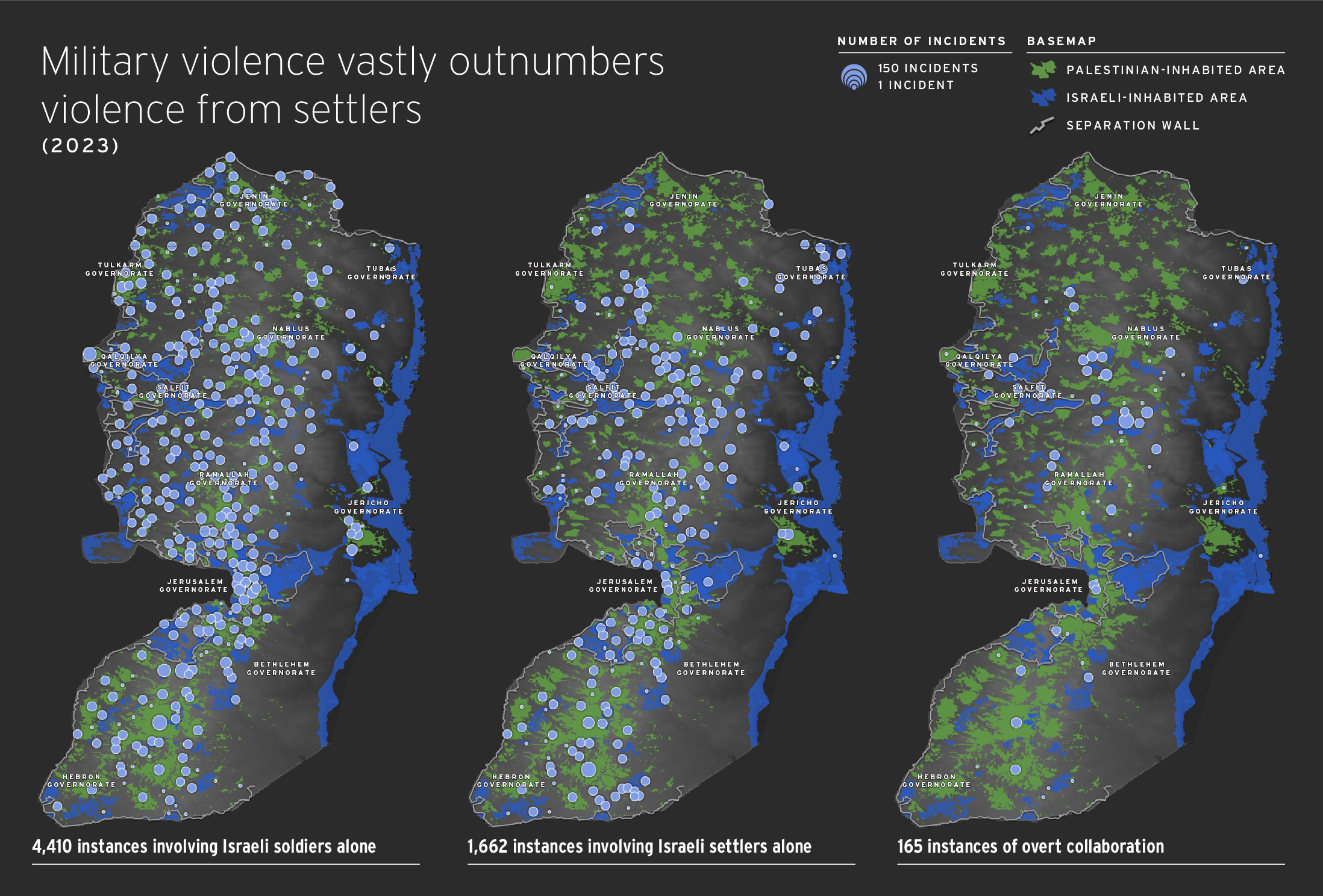

Israeli State Actors as Instigators

While the Israeli state often attempts to separate itself from the actions of settlers (a distinction recently amplified by several European counties and the United States who have begun sanctioning specific individual settlers as “bad apples”), the reality is of a strong overlap between Israeli state actors and settlers that exists on a spectrum from overt hand-in-glove coordination to implicit authorization of violence (Fig. 10). Far from keeping an unruly settler population in check, the Israeli military formed the backbone of the escalation from 2018 to 2020, as raids into Palestinian-inhabited areas outpaced the growth in violence by settlers by 85%, suggesting that the intensification of violence reflects a top-down Israeli state policy rather than the erratic action of zealous settlers alone. In 2023 there were 165 instances of overt coordination between soldiers and settlers across multiple categories of violence, from beatings to property destruction (Fig. 11).

A more common modality of this cooperation is the implicit permission that the military grants settlers to do violence. Recall that stone-throwing by Palestinians was met with riot control measures 72% of the time in 2023, while there was not a single recorded instance of the same against Israelis performing the same act. This and other forms of discriminatory enforcement produce an environment of tacit permission from Israeli authorities to Israeli settlers to treat Palestinians with impunity. Revealingly, in the rare cases in which the military does constrain settler violence, the settler reaction is extreme to the point of attacking Israeli soldiers (Fig. 12).

The settler-colonial violence committed by the Israeli military also has a qualitative effect, appearing to establish a baseline for the forms of violence settlers commit (Fig. 13).

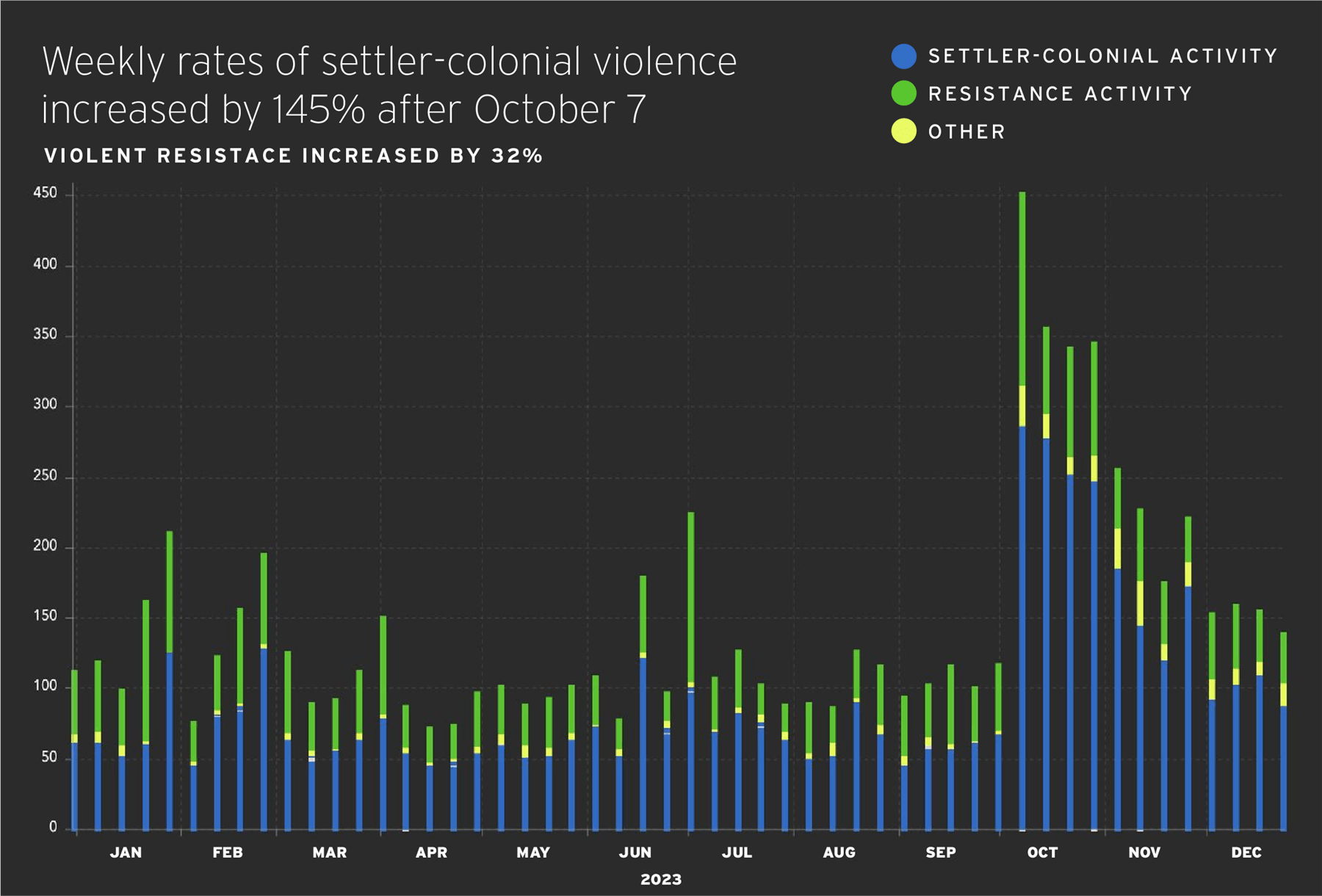

Changes Since October 7

The final weeks of 2023 saw an escalation in what was already an exceptionally violent year in the West Bank. Israeli-initiated events jumped from 66 to 161 weekly incidents, compared with only a 32% increase in resistance activity (Fig. 14). Israeli violence became more militarized overall, as live fire against Palestinian noncombatants leapt from 13 to 67 weekly incidents, weekly raids almost tripled, drone strikes became more frequent, and new checkpoint closures increased sevenfold. Driving the comparatively small increase in resistance activity were riots and insurgent attacks against Israeli military targets although, once again, 89% of such attacks occurred in the defense of Palestinian villages after October 7. Meanwhile, observed rates of activities initiated by Palestinians such as stone-throwing and attacks against settler noncombatants fell.

The massive spike in settler-colonial violence also took on new qualitative dimensions. Events where soldiers fired on or prevented medical personnel from rendering care doubled in frequency (Fig. 15). Housing demolition, a frequent tool of the occupation, became even more cruel as soldiers began forcing families to self-demolish their own homes or pay heavy fines (Fig. 16). Incidents where settlers forced Palestinian farmers to leave their land under threat of violence became five times more common (Fig. 17).

In sum, violence in the West Bank is largely a one-sided, asymmetric action inflicted by military, police, and civilian arms of the State of Israel. It unfolds almost exclusively where Palestinian live and work, in their homes, places of worship, and agricultural fields. It materializes in daily harassments, arrests, and destruction. When Palestinians resist through less violent means, their actions are condemned and their resistance is used to justify even more lethal violence.

Diplomatic cover, lack of international attention, and a cowardice to label this settler-colonial project truthfully are all necessary to fuel a status quo in which structured violence committed against three million Palestinians in the West Bank is normalized, to say nothing of the over 10 million diaspora Palestinians deprived of their right to return to their homeland. By placing the dashboard in the public and inviting users to query the data and develop their own readings of violent incidents, the Beirut Urban Lab makes a small contribution to the impressive efforts that media activists, counter-mappers, investigative reporters, and engaged journalists have made in the past months to correct flagrant biases and omissions in mainstream media. We join them in striving for just futures in Palestine.

References

[1] Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in the Gaza Strip (South Africa v. Israel) (International Court of Justice). Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/192/192-20240111-ora-01-00-bi.pdf

[2] Doumani, B. (1995). Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700-1900. University of California Press.

[3] Khalidi, R. (2020). The Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017. Metropolitan Books.

[4] Ibid.

[5] For more on the Israeli-enforced system of apartheid, see Yiftachel, O. (2023). Deepening apartheid: The political geography of colonizing Israel/Palestine, Frontiers Polit. Sci. 4.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.981867

Human Rights Watch (2021). A Threshold Crossed. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/04/27/threshold-crossed/israeli-authorities-and-crimes-apartheid-and-persecution (accessed May 27, 2022).

Amnesty International. (2022). Israel’s apartheid against Palestinians. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2022/02/israels-system-of-apartheid/

[6] For more on the politics of verticality, see Weizman, E. (2002, April 23). Introduction to The Politics of Verticality. openDemocracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/article_801jsp/

[7] For more on the apartheid legal regime see Al-Haq. (n.d.). Justice? The Military Court System in the Israeli-Occupied Territories. Al-Haq | Defending Human Rights in Palestine since 1979. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://www.alhaq.org/publications/8123.html

[8] For more on apartheid architecture, see Lambert, L. (2023). Teach-In: The Architecture of Settler Colonialism in Palestine. The Funambulist. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5QgxbFXUhCw)

[9] For more on settler colonialism in Palestine, see

Pappé, I. (2006). The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. Oneworld Publications.

Pappé, I. (2017). The Greatest Prison on Earth: A History of the Occupied Territories. Oneworld Publications.

Khalidi, R. (2020). The Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017. Metropolitan Books.

[10] Benjamin, R. (2020). Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the new Jim code (Reprinted). Polity.

[11] The Lab is prepared to share its re-coding of the ACLED data with interested researchers and investigative journalists.